Why Taiwan Power Company (TPC) decided not to chemically decontaminate its ChinShan Nuclear Power Station before decommissioning.

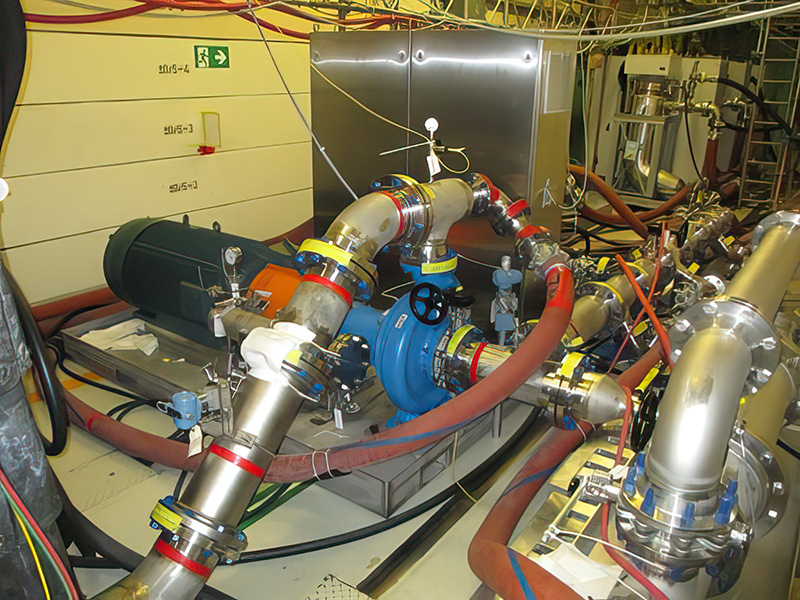

Completing a comprehensive chemical decontamination used to be standard procedure whenever a nuclear power plant was scheduled to be decommissioned. It made perfect sense. Plant operators wanted to ensure radiation exposure to workers who completed the decommissioning was maintained as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA). ALARA is a term the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in the U.S. uses to describe efforts to limit radiation exposure that prioritize human health and also take into account the technology at a power plant, the economics of reducing exposure, and a range of other factors.

“At first, everybody did it,” said Dr. Richard Reid, an EPRI technical executive who previously led chemical decontamination efforts at Maine Yankee, Michigan’s Big Rock Point, and Oregon’s Trojan nuclear power plants. “Dose rates then were relatively high, and plant operators felt they needed to get them down before decommissioning began.”

While worker safety was the primary driver of pre-decommissioning chemical decontamination, it was also a way to contain costs. Workers performing decommissioning can only be exposed to limited amounts of radiation. When dose rates are high in a plant being decommissioned, more workers will be needed, and additional protective gear and safeguards will be required, which can add significant costs.

Another upside to chemical decontamination before plant decommissioning is to proactively reduce the amount of radioactive waste that needs to be processed and managed. “You can reduce the waste classification of the material because you take most of the radioactivity off of the piping surfaces and other components,” Reid said.

A Move Away From Chemical Decontamination

Over the past two decades, though, chemical decontamination – which can also occur before maintenance work on a plant that remains operational – has become a far less routine practice before plant decommissioning. The main reason is that improvements in how nuclear power plants operate have reduced system radiation dose rates and, thus, worker exposure.

The reduction in worker radioactivity exposure has been so significant that chemical decontamination is no longer performed at any U.S. plants being decommissioned. In Europe and parts of Asia, chemical decontaminations of nuclear power plants are still performed, albeit in a reduced and strategic fashion. “Instead of doing the whole plant, they may just do certain very high dose rate areas,” Reid said.

When Taiwan Power Company (TPC) began planning the decommissioning of its ChinShan Nuclear Power Station in 2015, the utility assumed that it would complete a chemical decontamination. “TPC thought it was a standard practice of the decommissioning in general,” said Warren Chien, head of decommissioning section 1 at TPC.

But TPC paused before proceeding with plans to perform a chemical decontamination to understand better the costs and benefits of completing the decontamination and to survey how others in the global industry were approaching decommissioning. “TPC learned that the recent trend has been not to perform chemical decontamination in the U.S.,” Chien said. “We started to reconsider the necessity of the system decontamination.”

TPC had a strong rationale for investigating whether chemical decontamination in advance of plant decommissioning was necessary. The estimated cost of chemical decontamination at the two ChinShan Nuclear Power Station units was $20 million.

A Decision Guided By Research and Real-world Experience

To fully understand the factors to consider in its decision, TPC turned to past EPRI research, including the Nuclear Power Plant Decommissioning Sourcebook and the Decontamination Handbook, as well as technical guidance from Reid and others in EPRI’s Remediation and Decommissioning Technology Program. Taken together, EPRI’s decades of research and real-world experience decontaminating and decommissioning nuclear power plants provided a solid foundation for TPC to evaluate its options.

“We can guide these assessments with experience that we’ve built up over time. We have experience with both plants that did chemical decontamination and plants that didn’t do chemical decontamination. That full experience is quite important in these kinds of decisions,” Reid said. “That is really the crux of what we did with Taiwan Power Company. We gave them the insights we developed with our experience in chemical decontamination so they could use them to assess whether or not they should do it.” EPRI’s engagement with TPC involved analyzing each of the steps involved with decommissioning and developing an estimate of the worker radiation exposure that would occur at each step.

As part of its decision-making process, TPC relied on the EPRI Decontamination Handbook to perform a cost-benefit analysis on decontaminating the reactor recirculation system. The handbook provided guidance that decontamination is only financially worthwhile if average contact radiation rates are greater than a threshold value of 400 mR/hr. A TPC analysis found that the dose rates at ChinShan would be well below this value by the time decommissioning work commenced.

The Importance of Radioactive Decay

TPC eventually opted not to perform chemical decontamination at the ChinShan Nuclear Power Station. One big reason was that operational improvements at the power plant had significantly reduced radioactivity exposure rates to workers who would perform the decommissioning. Another driver for the decision was the future trajectory of radioactivity dose rates.

For example, cobalt-60 is a primary contributor to radioactive exposure. But its dose rates fall quickly over a short period of time. “Cobalt-60 has a half-life of five years,” Reid said. “After five years, the dose rates are naturally a factor of two lower than they were when the plant was operating. After ten years, they’re a factor of four lower; after 15 years, they are a factor of eight lower than when the plant shut down. Time and radioactive decay that happens naturally will give you the same benefit as chemical decontamination after about 15 years.”

TPC assessed dose rates in the reactor building and found they had decreased by a factor of two from 2015 to 2021, consistent with expectations. Given that the decommissioning work is not planned to begin for at least a decade after the power plants cease operation, TPC decided that natural radioactive decay would make chemical decontamination unnecessary. “TPC concluded that a minimum of 75 percent of the radioactive inventory in the reactor circulation system will have decayed away once the reactor building decommissioning commences and dose reduction in excess of 85 percent is highly possible,” Chien said. “Based on those facts, TPC utilized EPRI research and technical advice to evaluate the necessity and decided not to perform system decontamination.”

TPC will save an estimated $20 million by not completing a chemical decontamination at the ChinShan Nuclear Power Station. EPRI’s research and experience with TPC and many other utilities provides power plant operators with tools to make an objective decision about the value of chemical decontamination. “If cost is the main driver of the decision, that can be simple. It’s going to cost $20 million, and if my dose rates aren’t that high, I’m not going to do it,” Reid said. “But there are other benefits to doing chemical decontamination, and doing a comprehensive look helps you see what you’re missing by not doing it. Then, each individual utility can make their own decision about whether it’s worth it or not. And that’s going to be very country and plant specific.”

EPRI Technical Expert:

Richard Reid

For more information, contact techexpert@eprijournal.com.