The owners and operators of America’s more than 2,500 hydropower plants have unenviable to-do lists. On a day-to-day basis, for example, hydropower plant operators must manage reservoir levels, maintain critical dam infrastructure, and coordinate generation dispatch based on grid demands. Because the water in hydropower reservoirs is essential for many other uses—from agricultural irrigation to recreation to drinking water—continuous coordination with other stakeholders is a necessity.

Then there are all the longer-term decisions that demand attention. With many plant components nearing the end of their anticipated useful lifespan, structures and other equipment may need significant overhauls or replacement—tasks that require careful planning, extended procurement and design processes, and efficient implementation. “All of these tasks are competing for limited bandwidth,” said Dr. Mark Christian, an EPRI Technical Leader whose research focuses on hydropower.

As a result, integrating the potential impacts of climate change into planning—both for daily water management and long-term infrastructure decisions—becomes yet another challenge on an already full plate. The varying nature of climate change and its gradual, localized effects on precipitation levels make it difficult to incorporate those changes into hydropower operations and planning. “Climate change effects can seem very intangible. To many people, the specific effects and timelines can be nebulous – so what are people supposed to do about it?” Christian said.

Yet, decisions such as spillway capacity and reservoir operating rules will shape how plants perform for decades to come, and evolving climate factors may result in conditions that differ from those for which the plants were designed. However, to inform planning and potential investments, hydropower plant owners and operators require a clearer understanding of how potential future climate conditions will impact both plant performance and coordination with other sectors that depend on reliable water access.

While data is available on the anticipated impact of climate change on precipitation patterns, research has not specifically focused on how these changes may affect hydropower plants. “There’s a lot of forward-looking information on how precipitation might change, and there’s a lot of uncertainty there,” said Dr. Jacob Mardian, a researcher in the Energy Systems and Climate Analysis Group at EPRI, whose work focuses on the impacts of climate change on the electric power sector. “But not exactly on how reservoir inflows will change”.

A Screening Tool for Climate Risk

That’s why EPRI’s Climate READi initiative aimed to understand how a changing climate may impact the operation and performance of hydropower plants. The result of this work is a technical report, Climate Risk Indicators for Hydropower in the Contiguous United States, published in August 2025.

The research aimed to provide plant owners and the broader community with risk indicators relevant to each facility’s characteristics and potential future climate, thereby improving understanding of plant-level impacts, prioritizing infrastructure investments, and driving proactive collaboration with stakeholders. These quantified impacts include effects on both power and non-power services offered by hydropower, including generation, flood control, irrigation, navigation, and other critical services. To provide that kind of actionable information, EPRI leveraged a comprehensive streamflow dataset from Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), which was developed under the congressionally mandated SECURE Water Act. The ORNL data provided site-specific streamflow model projections for the period 1980-2099, while data on the characteristics of individual plants were obtained from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ National Inventory of Dams (NID).

The streamflow projections represent a range of potential climate futures rather than a single prediction. ORNL developed 28 different projections by running seven climate models under four emissions scenarios, ranging from aggressive reductions in emissions to expanded emission rates. Each model predicts daily streamflow data that has been calibrated against 40 years of historical observations. This approach captures the inherent uncertainty in climate projections while identifying trends that appear across multiple scenarios, giving operators a sense of both the range of possible outcomes and the likely changes they’ll need to prepare for.

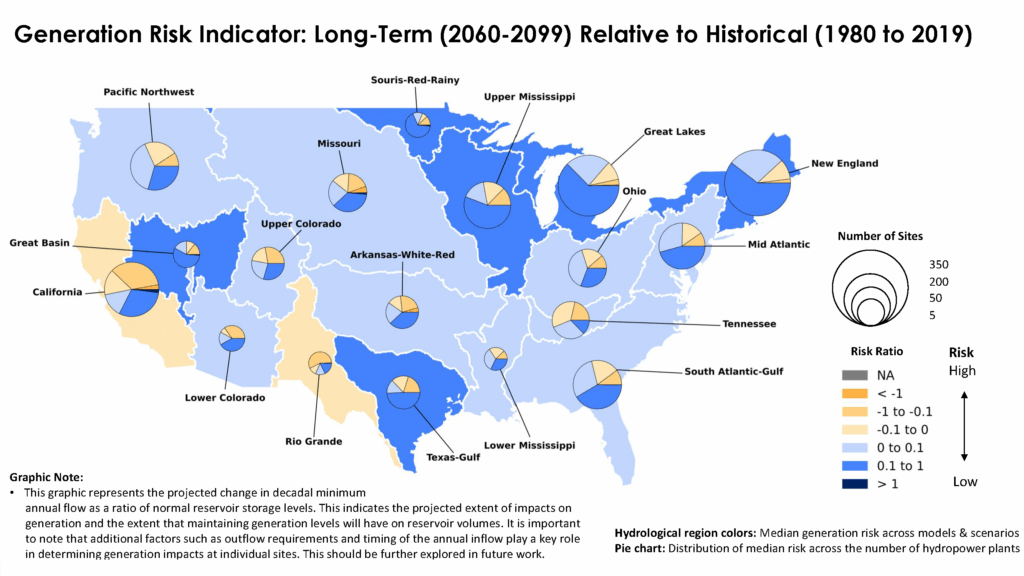

With this data, Christian and Mardian developed Hydrological Key Performance Indicators (HKPIs), metrics that connect projected hydrological changes to specific plant characteristics. At the individual plant level, this means that instead of simply calculating that the risk of drought may increase by a certain amount in the future, HKPIs consider the size of the plant’s reservoir storage. A large reservoir can typically manage drought better than a small reservoir in the same location due to increased water storage capability. The researchers assessed more than 1,400 plants individually, then aggregated the results at the watershed level. This was done to protect site-specific details and to identify regional patterns.

EPRI also partnered with the New York Power Authority’s (NYPA) Gregory B. Jarvis Hydropower Plant near Utica to demonstrate how HKPIs could support a more detailed analysis of climate impacts. The site was selected based on data availability and operational complexity to support adaptation of the model for other sites. Christian built a detailed performance model simulating daily operations at the plant, including reservoir dynamics, spillway operations, and water releases under calculated future water conditions. The level of effort required to create this model underscored the value of applying a screening tool fleetwide to help prioritize which plants are likely to need more detailed analysis based on site-specific risk.

Key Findings: A Complex Picture

While the purpose of the research is to provide individual plants with an assessment tool to understand potential climate risks, it also identifies more general impacts on generation, water supply, recreation, irrigation, flood control, navigation, and environmental sustainability relevant to facilities in different regions of the country. The results reveal a complex picture: climate impacts vary significantly not just between regions but even within individual watersheds. Some key findings include the following.

Generation. Overall, EPRI’s assessment found that most hydropower plants across the United States are likely to have increased annual water inflows, which could reduce generation risk. The Northeast showed the most significant increases in water availability, while the Southwest, particularly the Rio Grande Basin, faces the highest predicted risk of reduced flows. “We can see, even within this basin that has an increased risk calculation, there are some plants that have decreasing risk,” Christian said, pointing to the mixed outcomes the analysis revealed. Mardian noted an important caveat to these annual risk summaries: increased annual inflows don’t automatically translate to more generation if the additional water arrives during storm events or periods when reservoirs are drawn down for safety reasons and must be spilled rather than used for generation.

Flood control. A potential increase in flood risk, particularly during extreme events, is one of the most important takeaways. By examining both 100-year and 1,000-year flood scenarios, the assessment calculated increased risk of indicators in Southern, Southwestern, and Midwestern basins. “As the atmosphere becomes warmer, it holds more water, and you can get larger rainfalls, raising the risk of flooding,” Mardian explained. “That’s a change that is happening almost everywhere in the models.” The implications of this extend from dam safety, including investments to strengthen infrastructure to withstand flooding, to the importance of operators reevaluating how longer-term weather forecasts are integrated into reservoir management.

Water supply. EPRI’s assessment included 237 hydropower plants that provide municipal and industrial water and examined how low-flow conditions affect reservoirs used to supply water. Facilities in the Great Lakes and Upper Mississippi basins indicated increased risk of water supply shortages, especially in long-term projections. The interdependencies between hydropower plants, water supplies, and other uses warrant a more detailed analysis to understand the interaction between them in evolving climate conditions. “These are things we need to be studying in an integrated way,” Christian said. Advanced planning is necessary to manage water needs when they are most acute. Residential and commercial water demand peaks from June to October, which is often when regions face their lowest natural water availability. For plants with limited storage capacity, even modest changes in low-flow conditions can affect their ability to serve communities and industries depending on inflow, reservoir, and operational conditions.

Next Steps: Collaboration and Global Expansion

The EPRI assessment represents a first step in identifying the potential risks to hydropower plants from an evolving climate. While the analysis calculates which plants and regions face the greatest risks, translating those insights into action requires additional work.

EPRI is working to refine the HKPIs themselves based on feedback from the hydropower community. The initial HKPIs were developed using the best available data and expert judgment; however, Christian emphasized that each service that hydropower provides—from generation to irrigation to water supply—warrants a comprehensive investigation.

“We threw an H on the front, but really it’s a KPI,” he explained. “It is an indicator of broader system performance.” For example, the analysis measured extreme swings in water levels—either too high or too low—to assess the impact on reservoir recreation, assuming that both could disrupt activities like boating. But the real impacts are more nuanced and require input from local communities and the recreation industry.

EPRI is also working to expand the geographical scope of the work. Christian and Mardian have proposed research to build AI-based models that would extend the climate risk assessment to hydropower plants internationally, particularly in countries that lack the comprehensive streamflow projection datasets available in the United States. EPRI is also collaborating with ORNL on a follow-on assessment examining how climate change may affect dam breach risk.

Most importantly, the work establishes a pathway from fleetwide screening to detailed site analysis. The development of the NYPA model demonstrates that, once priority plants are identified through the screening process, the detailed operational modeling approach can be tailored to those facilities. “Climate change is an uncertain and evolving science,” Mardian noted. “This is not something you do once and check the box. Asset owners need to periodically monitor and update their risk assessments.” The screening tool provides a framework for that ongoing evaluation, helping operators move from recognizing that climate change is happening to understanding what to do about it.

EPRI Technical Experts:

Mark Christian and Dr. Jacob Mardian

For more information, contact techexpert@eprijournal.com.