It would be difficult to imagine power plant locations more opposite than the East River in downtown Manhattan and the Mobile River in rural Alabama. Con Edison’s East River Generating Station operates in one of the densest urban landscapes on the globe. In contrast, Alabama Power’s James M. Barry Electric Generating Plant operates in a rural environment in the Deep South.

Although in vastly different settings, the two plants recently shared something important: the need to reduce potential harm to aquatic life from the use of river water for cooling while simultaneously protecting their cooling water intakes from clogging by waterborne debris and biofouling. Both plants are preparing to comply with new U.S. Environmental Protection Agency rules on intake structures for existing facilities, finalized last August. Con Edison also must comply with requirements of a state-issued permit allowing continued operations without a cost-prohibitive retrofit of a closed-cycle cooling system. Both utilities turned to EPRI, a research leader in the area, for assistance.

Manhattan-Style Fish Protection

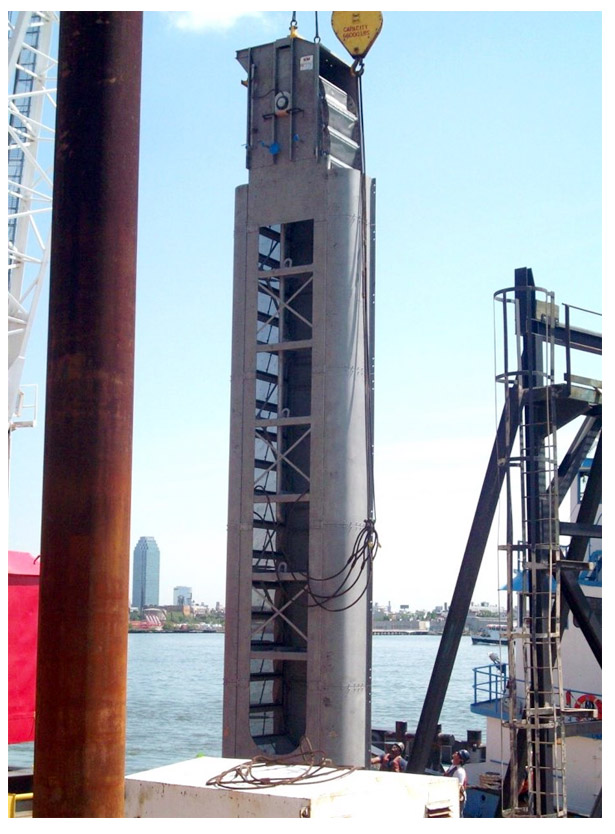

For two decades starting in 1989, Con Edison’s East River Generating Station relied on traveling water screens to prevent debris from being swept into its cooling water intake structure and potentially shutting down the plant. In 2009, the state required Con Edison to upgrade its screens to maintain its State Pollution Discharge Elimination System permit.

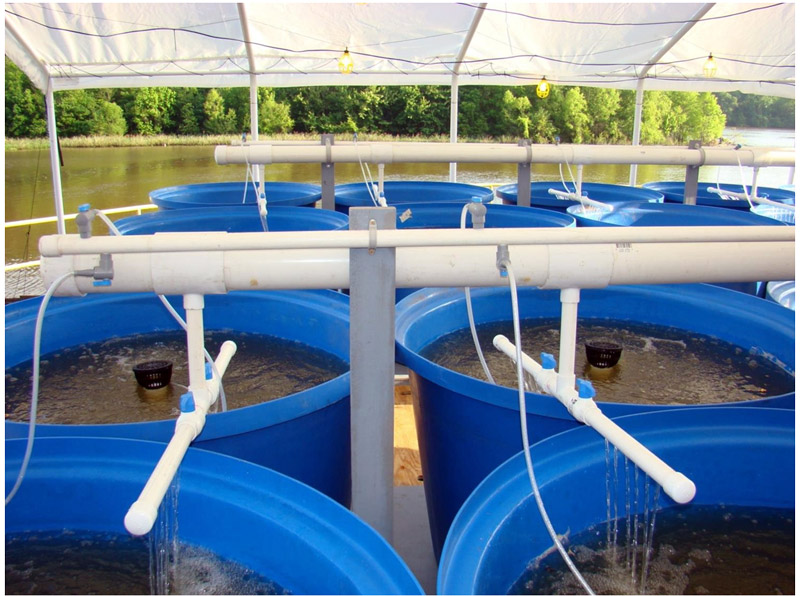

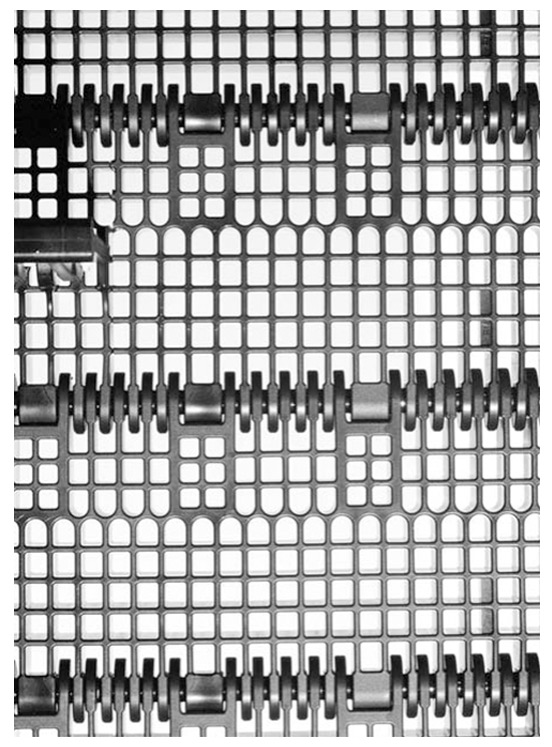

For years, EPRI has conducted collaborative fish protection research as part of its mission to make electricity more environmentally responsible. Building on knowledge from these efforts, EPRI worked on research with Con Edison to optimize the utility’s new fish protection–modified traveling water screens and fish return system. Prior to modification, the screens rotated intermittently from underwater to the surface, where collected debris and fish were washed into a combined trough for return to the river. Through several iterations, Con Edison and EPRI worked together to make the screens more fish-friendly, including using woven mesh metal screens that are not as abrasive for the fish, collecting fish in buckets on the screens, and continuously rotating the screen so fish can be removed quickly. As the rotating system raises the fish, they are rinsed from the screens with a low-pressure wash system into a trough that returns them to the river. In addition, when fish eggs and larvae are present during spring and summer, finer mesh screens are used to prevent entry into the plant’s cooling system. They are also rinsed from the screens and returned to the river to continue their growing phases. Because the system is significantly safer for aquatic life, Con Edison expects to achieve compliance with its permit after it completes a monitoring plan to demonstrate the new system’s performance.

Southern-Style Fish Protection

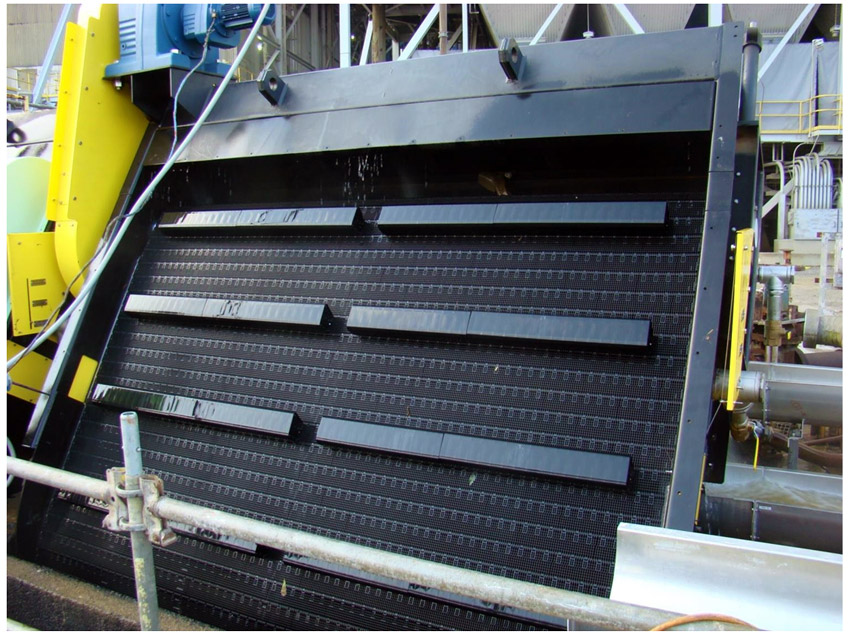

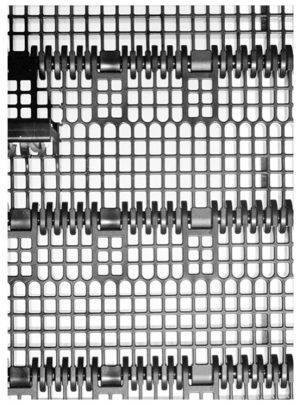

As with Con Edison, optimizing fish protection was at the core of EPRI’s collaboration with Alabama Power, which also installed fish protection–modified traveling water screens at its Barry Electric Generating Plant. Instead of metal screens, the utility opted for a version manufactured by Hydrolox and made with a much lighter molded polymer. The utility faced a severe debris problem, and the polymer screen’s design and material offered the potential to shed sticks and protect aquatic life more effectively.

Barry’s cooling water intake structure was the first to complete a retrofit using this technology. EPRI and Alabama Power conducted a research study to gauge the screen’s debris-handling and fish protection performance, providing a model for future analyses. Alabama Power’s parent Southern Company funded the study, along with Dairyland Power, Luminant, and Omaha Public Power District. “This was an excellent example of how EPRI’s collaborative R&D model can demonstrate a new screening technology,” said EPRI Technical Executive Doug Dixon.

For their fish protection work, both Con Edison and Alabama Power received EPRI Technology Transfer awards.

EPRI Technical Expert:

Doug Dixon